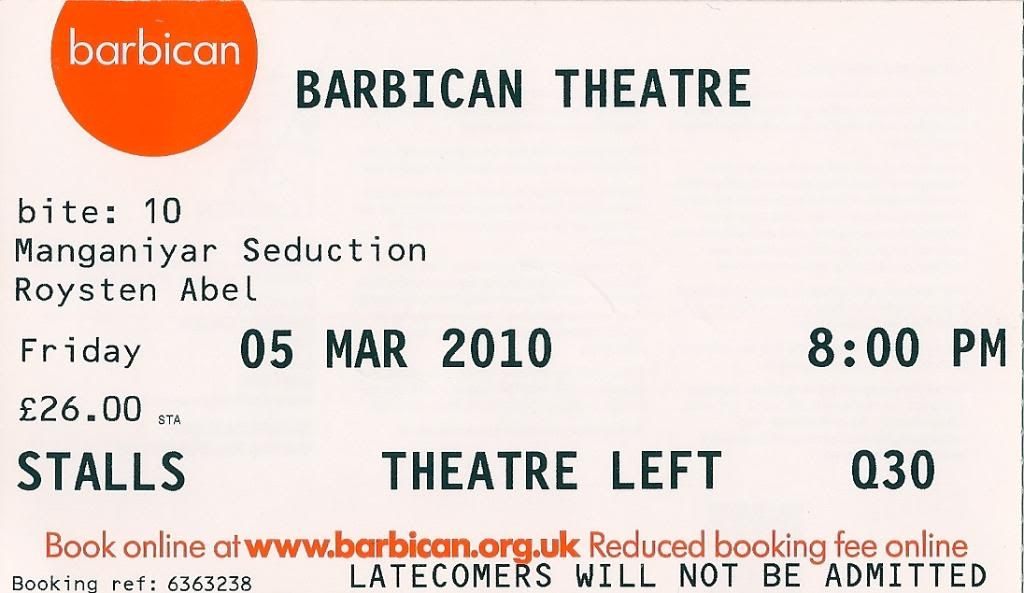

Thirty six boxes, stacked four storeys high, containing 43 Rajasthani desert musicians. Yes, the Manganiyar Seduction is nothing short of spectacular. Staged by director Roysten Abel, the show brings an incredible theatricality to the performance of traditional Indian Sufi music, and I was fortunate enough to catch it on the first of its three night run at the Barbican Centre as part of the East festival and bite: 10.

Beginning with a solo musician, the production gradually built to an almighty climax as the 42 other musicians unveiled themselves from behind their curtains. Housed within a set which undoubtedly drew influence from Jaipur's Hawa Mahal and Amsterdam's red light district, these musicians were led, with tremendous gusto, by conductor-cum-dancer Daevo Khan. It was he who broke the formal delineation between the audience and the performers and was crucial in providing the energy which engulfed the theatre. He, rather deservedly then, drew his own applause.

After the performance, Abel came on stage to briefly provide context for the production. He explained how the Manganiyars are a caste of Muslim musicians from North India who also worshipped Hindu deities. Their music, he continued, fuses folk and classical genres and was traditionally performed for the kings of Rajasthan. His discussion was brief but insightful and was spliced with personable segments of humour in which acknowledged the difficulties which they faced whilst globally touring the production - getting 43 Muslim's through immigration control was no easy task, he joked.

What I will admit is I couldn't help but feel as though Abel's contextualisation of the work should have come sooner. I say this because of a number of reasons, firstly the staging provided no clues about the music's meaning, secondly there was no emcee nor were there subtitles, and thirdly programmes were only distributed as the audience left the theatre, therefore we, as audience members, were simply listeners in the broadest sense of the term. A more enhanced acknowledgement of the cultural distance between the musicians and the music which they were playing, and the audience to whom they were playing it to could, and should, have occurred from the get-go. Unfortunately as a result, the piece fell slightly short in terms of context or grounding.

Regardless, I remained mesmerised throughout - mesmerised by the colour, by the intensity of the music and by the production's originality - and as the audience unanimously rose to their feet in rapturous applause, I knew I was certainly not alone.